One thing I encounter among Catholics on social media is the assumption that: because I identify with a thing, it must be good or because I oppose it, it must be bad. The problem with this view is it confuses what makes an act good or evil objectively with one’s feelings about an act. Since people don’t like to think of themselves as being wrong, this assumption frequently results in accusing the Church of error for affirming a teaching in the face of popular sentiment.

These attacks—like so many others—are not limited to one region or faction. Conservative or liberal; Democrat or Republican; these and many other factions across the public square find fault with the Church where the Church cannot do anything else but teach this way.

To understand why the Church holds that a thing must be a certain way, we need to grasp that there are three things needed to make an act morally good. The action itself must be good (e.g. you can never say an act of rape or genocide is good), the results must be good (a do-gooder who sparks a riot through lack of prudence doesn’t perform a good act even if the action itself is good), and the intention must be good (If I donate money to charity in order to impress and seduce my neighbor’s wife, that is an evil intention). If even one of these three conditions are absent, you don’t have a good act. Let’s look at some illustrations.

Things like abortion are examples of an intrinsically bad act. It arbitrarily chooses to end an innocent human life for the perceived benefit of another human life. Even if the person who commits it thinks that the good outweighed the evil, or meant well in doing so, you can’t call it a good act. How one feels about it doesn’t change that fact. This is why the Church cannot do anything other than condemn it. Reducing the amount of abortion cannot be an end in itself. It can only be a step on the way to abolition†.

Other acts can be neutral or good in themselves, but the consequence is bad. For example, the Church does teach that a nation can regulate immigration if doing so is necessary. This is something critics of the Pope and bishops love to point out. But there is a difference between “our country is in the midst of a disaster and we are having trouble dealing with it right now” and “Criminals among THOSE people are dangerous and we don’t want them here, so let’s keep everyone out!” The US bishops are pointing out that America is not in that first situation, and the second situation is a morally bad consequence—refusing to help those in need out of a fear of who might get in.

And, of course, a good or neutral act can be made bad if done for a bad intention. Being thrifty is a good thing. But, if one is frugal for a bad reason (like Judas dipping into the common purse [John 12:5-6]), it’s not a morally good act. If a government cuts expenses with the intent of targeting certain groups or raising taxes in the name of social services, but defines the term to fund immoral policies, then the bad intention corrupts the good or neutral base act.

In these cases, no matter how much one identifies with the cause, if it’s defective in one of these three parts, you can’t call it a good act.

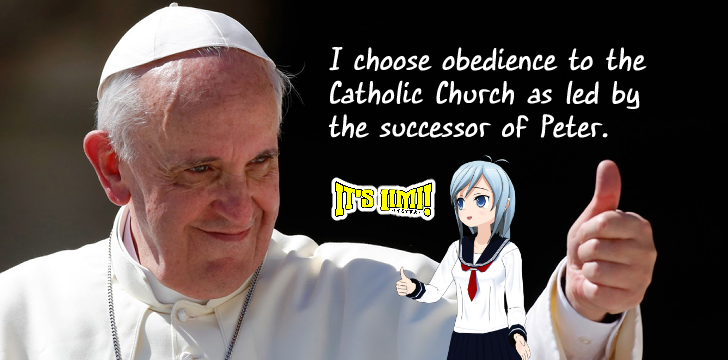

On the other side, the fact that the Church as a whole, the Pope, or an individual bishop‡ acts in a way we disagree with does notmake it a morally bad act. The Church needs to act with an eye towards saving souls. That might be a soft merciful approach, as when Our Lord dined with sinners. It might be a strong rebuke, as when Our Lord rebuked the Scribes and Pharisees. But the point of their action is supposed to be bringing the sinner back to reconciliation. Since the Church is made up of sinners with finite knowledge, we will invariably encounter situations handled badly. But we will also encounter situations we think are handled badly due to our own lack of knowledge… either about the situation or about the teaching behind the Church’s action.

Every election year, for example, we hear from certain Catholics on how the bishops are failing by not excommunicating politicians for supporting abortion. This is based on a misunderstanding of canon law. Canon law points out that those directly taking part in a specific act of abortion (abortionist, their staff, woman having an abortion, etc.) are automatically excommunicated. But those working to protect abortion as a “right” are doing something gravely sinful and, under canon 916, should refrain from Communion. Canon 915 involves those publicly involved in grave sin. Some bishops have invoked it in refusing communion to politicians in their dioceses. Others don’t seem to have acted in this way.

But what we don’t know is why they have not acted publicly. It could be laxity or sympathy… the two common charges from those who demand public action. Are there situations we don’t know about? Are the bishops in personal dialogue with these Catholic politicians? Have they privately told these politicians not to receive? Do they want to avoid conflict? I don’t know… but neither do the critics. We should certainly pray for our bishops to shepherd rightly. But we should also keep in mind that—in connecting the dots—we may not have seen all the dots that we need to connect.

This should not be interpreted as a “be passive in the face of injustice.” What it means is, we should not be so confident in our interpretation of events that we think only the conclusion we draw is true. Church history is full of people who thought they knew better and caused all sorts of chaos, endangering their own souls and the souls of others. Because conditions change, the Church will have to decide how to best apply timeless truths to the current times. Sometimes, the attitudes of a society can lead Catholics to tolerate—or even commit—injustice. Sometimes those Catholics are higher up in the Church. But we must not assume that this is the case when the Church must teach in a way we do not like.

_______

(†) Of course, we must do more to help people than just end abortion. We need to help people in situations where they think it is the only choice. But only focusing on those parts while leaving it legal is not a Catholic position.

(‡) Provided, of course, the Bishop is acting in communion with the Pope and fellow bishops. The actions of a Lefebvre or a Milingo (for example) cannot be defended on these grounds.