Saturday, July 29, 2017

Friday, July 21, 2017

The Hudge and Gudge Report

G.K. Chesterton, in his book What’s Wrong With the World (Chapter IX), offers an account of two men—Hudge and Gudge—who desire to help the poverty stricken. Hudge sets out to build massive housing blocks that meet the physical shelter needs but are deeply oppressive. Gudge objects to the oppressive nature of these apartments and says they lack the character of the former homes. As time progresses, Hudge begins to defend the worst parts of the apartments as good, while Gudge begins to proclaim that people were better off living in the slums. Finally they reach the extremes where Hudge thinks all people should be living in these apartments and Gudge believes that poverty is good for people.

I find the account to be useful in examining the growing divisions and rigidity of factions. But, there is always the danger of thinking that “the other guy” behaves like Hudge and Gudge while we are defenders of truth and right. The problem is, Hudge and Gudge also think the problem is with “the other guy,” while they have the real solution. If we’re blind to our own rigidity, refusing to consider where we go wrong, we are in danger of corrupting our ideals.

This is especially true when Christianity intersects with determining moral state policies. Because the major political factions tend to be right on some issues and wrong on others, we tend to gravitate towards those factions that agree with what we think are the most important issues. But as factions get more extreme, it is easier to downplay the issues where the other party is right.

For example, I know some Catholics who are appalled with life issues besides abortion and euthanasia. They insist that all Catholics recognize these issues as important. But growing more rigid, they begin to downplay the actual issues of abortion and euthanasia. Some have gotten to the point of being more outraged at Catholics who are “anti-abortion but not pro-life” than by Catholics who are literally pro-abortion. But, on the other side of that fight, Catholics who recognize the evil of abortion and euthanasia fall into the trap of going from recognizing that those two issues are the worst evils to thinking other life issues are “not important.” Both of them are wrong when they go from promoting some issues they feel are neglected to neglecting the issues they think are less important. It becomes dangerous for the soul if it leads these people to think that others who oppose a moral evil are partisan.

It doesn’t have to be about morality vs. politics either. It can also be, for example, the cause of liturgical wars. The Ordinary vs. Extraordinary form of Mass is a common battleground where some Catholics have become so involved in defending their own position that they refuse to consider the good from the other position. The defender of the Extraordinary Form is tempted to treat the Ordinary Form of the Mass as “clown masses” and other liturgical abuses. The defender of the Ordinary Form is tempted to view the Extraordinary Form as the haven for schismatics.

We need to realize that both of our major political factions are a mixture of some good and some evil. We need to realize that both forms of the Mass have good to offer the Church, and some weaknesses that need to be overcome. If we solidify to the point where we think that good is only found in our faction, but not the other, we risk embracing the evil of our own faction and rejecting the good in the other: once we reach that stage, we’re giving assent to—or at least tolerating—evil in our faction, and rejecting good when it comes from another faction. That is incompatible with God’s teaching, but we will have blinded ourselves to our disobedience. It saddens me, for example, when I see some Catholics say, “We’ll never eliminate abortion so we should focus on other issues,” or that “pro-abortion politicians support policies that reduce the need for abortion.” This is Hudge and Gudge thinking. But so is thinking that says that “so long as abortion is legal, we can’t worry about other issues.”

The only way to escape this is to get rid of our Hudge and Gudge thinking. We need to recognize that our factions must be judged by Church teaching, and not that Church teaching is judged by our factions. If we believe that the Church stance on abortion and “same sex marriage” is proof the bishops are “Republican,” we’ve fallen into the Hudge and Gudge trap. If we think the Church opposition to the government position on immigrants is “liberal,” we have fallen into the Hudge and Gudge trap.

If we profess to be faithful Catholics, the Church must be our guide into right and wrong, because we believe that God gave the Church His authority and protects her from error. If we consider the Church teaching as the way to form our political judgments, we might be able to support the good in our preferred political factions while opposing the evil. We might also seek to reform the system rather than to just tolerate the least possible evil as the best we can hope for.

This means we must reject our partisan rigidity and be always open to the Church calling us to a firm standard of good and evil, while also being open to different ideas of carrying them out. We never compromise on doing what is right or being faithful to the Church. But we can consider whether our factional preferences are in the wrong. If they are, we must choose the Church over our preferences or factional beliefs. And if our factional opponents are not wrong, we must stop treating them as if they were.

Thursday, July 20, 2017

Sunday, July 16, 2017

It's Time to Take Back the Faithful Catholic Label (and the means are different than one might think)

Introduction

On the internet, a battle rages over what image the Catholic Church should take. Some are all about changing Church teaching. Others are about preferring the older way to do things. But whether these factions are politically conservative or liberal; whether they are modernist or radical traditionalist, or some other faction, they assume they are the ones really being faithful to the Church, and that those who think the preferred faction are wrong are accused of not being faithful. The problem is, this decree is not a decision of the Pope and bishops issuing a teaching. This is the claim of factions that are in opposition to the Pope and bishops. In other words, the Catholics who claim they are really being faithful are the ones who are refusing to assent to the teachings they dislike, and claim that their disobedience is really some sort of higher obedience.

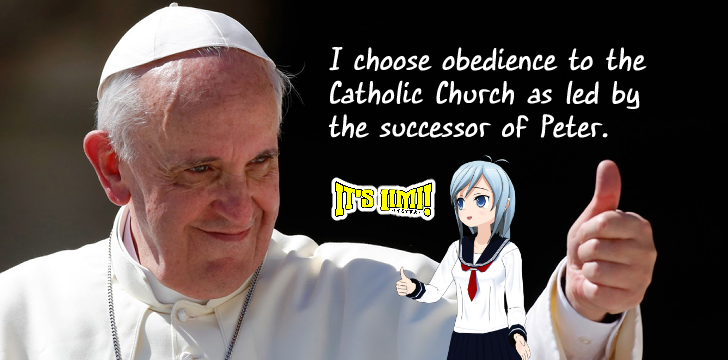

The problem with this claim is: Church history has never recognized the actions of such dissenters as being “truly faithful.” The saints who reformed the Church gave obedience to the successors of the apostles, even when the men who held the office did not personally behave in a manner worthy of it. There is a (possibly apocryphal) story of St. Francis of Assisi meeting Pope Innocent III. Disgusted with the saint’s appearance, he reportedly said to go and roll with the pigs. St. Francis obeyed, impressing the Pope with his obedience and humility. Our 21st century sensibilities rebel against this, but St. Francis, recognized as one of the saints that reformed a Church in danger of becoming worldly showed that one cannot claim to be a faithful Catholic while refusing obedience to the Pope.

There is a vast difference between the saints who showed obedience to the Church out of love of God and the dissenters who declare themselves superior to the shepherds in the Church, and we need to take back the label of “faithful Catholic” from these counterfeits.

The First Steps

You might think the first step is to denounce the dissenters. But that would actually be following into their error—putting confidence in their own holiness. We should consider well the words of St. John Chrysostom, in his homily on the Gospel of Matthew:

Nay, if thou wilt accuse, accuse thyself. If thou wilt whet and sharpen thy tongue, let it be against thine own sins. And tell not what evil another hath done to thee, but what thou hast done to thyself; for this is most truly an evil; since no other will really be able to injure thee, unless thou injure thyself. Wherefore, if thou desire to be against them that wrong thee, approach as against thyself first; there is no one to hinder; since by coming into court against another, thou hast but the greater injury to go away with. (Homily LI, #5)

John Chrysostom, “Homilies of St. John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople on the Gospel according to St. Matthew,” in Saint Chrysostom: Homilies on the Gospel of Saint Matthew, ed. Philip Schaff, trans. George Prevost and M. B. Riddle, vol. 10, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, First Series (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1888), 320.

Our first thought should not be on the injuries others have inflicted on us, nor on “getting our own back.” Our first thought should be on where we ourselves stand before God. Because we are sinners, we cannot think of ourselves to be righteous before God. But because of God’s love for us, we cannot of others as being less deserving of His forgiveness. If we forget this, we become like those who misuse the term “faithful Catholic.”

We must also seek to learn as much as we can about the faith. Now the writings of the Saints, the Popes, the Councils and the Bishops are vast. No one person could read them all—and that’s something we need to learn: That we do not know everything. We can always learn, and our teachers must be those who have the authority to bind and loose—not bloggers or academics who disagree with them.

Knowing that we do not know everything does not mean that it is possible that Church teaching can justify something we thought was a sin. What it means is we need to recognize we can be led astray by laxity or rigorism if we do not understand that the Pope and bishops teach with the same authority that Our Lord gave the apostles. They have the authority to teach and govern the Church. When they do, we must assent to their teachings. Refusal to do so is schism:

can. 751† Heresy is the obstinate denial or obstinate doubt after the reception of baptism of some truth which is to be believed by divine and Catholic faith; apostasy is the total repudiation of the Christian faith; schism is the refusal of submission to the Supreme Pontiff or of communion with the members of the Church subject to him.

Code of Canon Law: New English Translation (Washington, DC: Canon Law Society of America, 1998), 247.

If we would be faithful Catholics, we must realize our own sinfulness and our own limits to knowledge. Knowing this, we can turn to God for His grace and forgiveness. Knowing this, we can turn to His Church to learn what we must do to be faithful.”

But What About the Internet Brawls?

Speaking personally, I’d be happy if I never had to take part in another one. But we will encounter some who are either mistaken about the faith or are misrepresenting it. When these situations arise, we should remember 1 Peter 3:15-16:

Always be ready to give an explanation to anyone who asks you for a reason for your hope, but do it with gentleness and reverence, keeping your conscience clear, so that, when you are maligned, those who defame your good conduct in Christ may themselves be put to shame.

If someone’s going to act like a jerk, strive to make sure it isn’t us. If we want to put a verbal smackdown on our opponents, we risk leaving the audience thinking we’re both jerks.

When we encounter those dissenters who claim to be the “true” faithful, the temptation exists to “put those jerks in their place.” But we must not take that attitude. This is partially because we risk being overcome by pride, thinking we are fine as long as we are not like “them.” But also because we risk alienating the people we hope to help. Now, being sinners, we’ll always have problems. I can describe these dangers because I have fallen into them myself.

So, when someone decides to attack the Church, or the Pope, we must not allow ourselves to flail wildly, or speak viciously. We may have to tell a critic, “We do not believe what you accuse us of believing.” We may have to explain the truth. This may not be effective with the person we are arguing with. But that person is not the only person involved. On the internet, there are more lurkers than commenters. Even if our adversary is not willing to listen to us, the lurkers might—if we give them a reason to. But if we’re rude and abusive, we might win some points with people who already agree with us for doing a stylish smackdown, but we won’t convince others.

Conclusion

How do we take back the label of “faithful Catholic” from those dissenters who claim to be in the right while the Church is in the wrong? As I see it, we have to act like faithful Catholics. That means following the example of the saints in their obedience and humility. If we want to convince people to be faithful Catholics, we have to give them a living example.

That means, turning to the Lord with the desire to repent and follow Him anew, seeking to know and do His will as taught by the Church. Not by what we think the Church taught at a time we think most pleasing to follow.

Saturday, July 15, 2017

Assumptions: Winding Up in the Ditch (Luke 6:39)

When it comes to hostility or suspicion towards the Church, regardless of what side it comes from, it is rooted in assumptions, not fact. People assume they understand what the Catholic Church holds, or assume they understand the words of a member of the Church that they oppose. Such people assume that not seeing other possible meanings means there are none. They assume that the Church/Pope/Council must be in error if they don’t match what the critics think should be. But, what they fail to consider is whether their own understanding about what should be is correct. For example, if Martin Luther was wrong (and I believe he was) about what God intended the Church to be, then the way he went around attempting reforms was fatally flawed, even if he meant well.

I believe the same is the case with the modernist Catholic who believes Church teaching on things that are intrinsically evil can be changed and the radical traditionalist who believes that the Pope is a heretic. They start with the assumption that what they think about God and what His Church should be is true, and assume that, if the Church is not what they think it should be, the Church has “fallen into error.” But, as with my above example with Luther, if the critic’s conception of what the Church should be is false, then their ideas are also fatally flawed.

These critics do not have to be malicious. They can be quite sincere. But if they are mistaken, unwilling to consider the possibility of being in error, they will be like the blind guides Our Lord warned against. They will lead the other blind man into a pit (Luke 6:39). Not because they wish to do harm, but because they wrongly think they know the way when they need help themselves.

I find that when it comes to disputes of this kind, we don’t have two errors. We have one: but the people in error simply disagree over whether that mistaken view they think true is a good thing or a bad thing. If the view is mistaken, then these people are worked up over nothing. I believe that the case of Vatican II and Pope Francis illustrate this point. Some Catholics wrongly believe that the Council intended to change everything, but Popes Blessed Paul VI, St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI “betrayed” the Council. Others believe that the Council not only intended but did change everything, and blame Popes Blessed Paul VI, St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI for helping aid the “destruction” of the Church [†].

Needless to say, they can’t both be right. But they overlook the possibility that neither can be right. Since both believe that Vatican II was a radical break, both are in error if Vatican II was not a radical break. Since both believe Pope Francis intends to change Church teaching, both are in error if he does not intend to change Church teaching. The assumption is that these things are so, but that assumption is the point that has to be proven. We cannot conclude that the conclusions drawn from those assumptions are true when they are unproven.

But instead of proof, we get fallacious arguments. For example, “Well, if the Council didn’t mean that, why did this rebellion happen?” That’s the point to be investigated, to see why and how it happened. Invoking Vatican II as the cause of rebellion is meaningless if it never intended what people claim. The point is, it is not what people think the meaning is. It is what the intended meaning is. If people are wrong about the intended meaning, their conclusion is wrong too.

The point of all this is, if we place ourselves in opposition to the Church, and assume we are in the right, we will go wrong. The Church is given the task of preaching the kingdom to the world, and is given the promise of Our Lord’s protection. To accuse the Church of teaching error is to deny Our Lord’s power to keep the promise, and I find that blasphemous. That’s the case if the accuser is saying the Church is wrong on sexual morality, or if the accuser is saying the Church is wrong on Vatican II.

The only way we can avoid winding up falling into the ditch is to stop assuming we are a better guide to salvation than the Church. This means we stop assuming we know better than those chosen to shepherd on how to interpret what the Church has always taught and how to apply it in our own age. The Church has been given this task, and the Church has been given the protection to carry it out. Following any source in opposition to the Church is to follow a blind guide.

It really is that straightforward.

_____________________________

[†] Oh yes, people forget it, but these critics savaged Blessed Paul VI, St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI just as much as they savaged Pope Francis.