I’ve seen an argument going around that tries to justify accusations against the Pope. This argument runs along the lines of “If the Pope didn’t believe X, he should have said something to refute it. Because he didn’t say something, it must be true.” The people who make the argument think it’s proof for the claims made by Scalfari or Vigano. Others have used it for the dubia from Cardinal Burke and others, arguing that since the Pope did not answer it, he could not answer it.

The problem is, it’s a logical fallacy: The Argument From Silence. This fallacy assumes that if there was anything that could refute their position, then it would have been issued. Since it wasn’t issued, it means there’s nothing to refute it.

This argument overlooks the fact that the Pope is not required to give an answer and may choose not to for different reasons. Sometimes he has allowed his staff to issue the refutation. Sometimes the question was disrespectful in tone or means of distribution, not meriting a response. Sometimes the question is so stupid as to be unworthy of a reply. Perhaps in some cases, the decision not to answer is an imprudent one. But that’s something that the Pope must determine.

The point is: Silence neither proves something is true or false. Silence is simply an absence of proof.

The Second Fallacy: Begging the Question

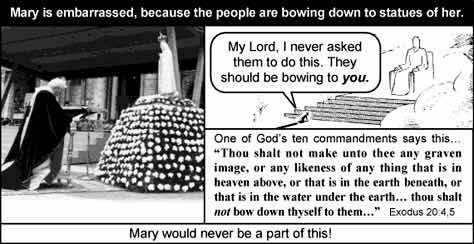

“Why is Mary Crying?” by Jack Chick. Modern critics are repeating his errors by assuming such acts must be latria.

At the same time that they accuse him of silence, certain critics accuse him despite his response denying their charges. Based on their interpretation of what we all see, they accuse him of “promoting paganism.” To “prove” their point, they provide links to Wikipedia and other sources about Pachamama. They tell us, “See? Pachamama is a pagan idol, therefore the Pope is guilty of promoting idolatry!”

The problem is, these critics are starting with an assumption (apparently originating with an Evangelical§ indigenous chief) that this image was an idol and that all acts of prostration are acts of worship, regardless of culture. These are the points that need to be proven. But, instead of investigating the origin of the image, the religious affiliation of those performing the ceremony, and how it was used before coming to Rome, critics repeat the mantra that it was an idol and cite references against idolatry to “prove” that the Pope is guilty of idolatry. But those “proofs” are only of value if it is established that the object was an idol. But that’s assumed, without the proof needed to justify the accusation.

The Third Fallacy: Appeal to Irrelevant Authority

If one wants to invoke a big name in the Church in this matter, one must ask whether their authority is relevant to the matter at hand before one can accept their claims as authoritative. Certainly the priests, bishops and cardinals are to be heeded when they are acting in communion with the Church and the Pope. As Lumen Gentium #25 explains:

Bishops, teaching in communion with the Roman Pontiff, are to be respected by all as witnesses to divine and Catholic truth. In matters of faith and morals, the bishops speak in the name of Christ and the faithful are to accept their teaching and adhere to it with a religious assent.

Certainly, when members of the magisterium act in this role, they are to be listened to. But, while giving all due respect to them, clerical critics like Father Mitch Pacwa, Bishop Schneider, and Cardinal Burke@ (those most commonly cited by the most vocal critics on social media) are not experts on the culture and religion of the Amazon region. Moreover, they are offering their opinion#, not speaking in their role as teachers in the Church. If it was intended to be a pagan act of worship (see the Second Fallacy above), then their concerns have merit. But that has to be proven before we can accept their claims.

The Fourth Fallacy: Straw Man

“Aha,” some critics exclaim. “The Pope called it Pachamama. Therefore he proved the charge!” Well, no. The Pope used the common term bestowed on it by the Italian media for purpose of identifying which object he was referring to. Unfortunately, there are no neutral terms in use. For example, to avoid a similar problem, I choose to use the terms “image” or “object” to refer to it, only using the term “Pachamama” is quotation marks*. But it’s not a universal standard and I have to clarify which item I mean. I would certainly be annoyed if someone took my use of the term image to mean “religious image.”

Since the Vatican press office (that’s their job, see The First Fallacy, above) had stated the Pope did not use the term to identify the object as an idol, it should be a case of Roma locuta, causa finita.” But certain people refuse to accept that they misinterpreted him and insist on repeating their arguments as if the correction of their errors never happened.

The Fifth Fallacy: Ipse Dixit

Not all dogmatic statements are ipse dixit. One who teaches with authority (the Pope, the bishops in communion with him and teaching in accord with him) can make statements that are binding (see canons 752-754). That’s not because of their personal wisdom, but because of the authority granted their office by Christ. Experts in a field can be cited in their areas of expertise in a limited extent because they are explaining the vetted knowledge in their field. But if they should speak on matters outside their field (the Pope offering stock tips, scientists speaking on religion, actors speaking on politics), what they say does not have authority.

But those who are not experts teaching in their field or speaking with the authority of their office within the Church cannot expect that a statement of theirs be accepted without question.

How does this differ from the fallacy of irrelevant authority (#3, above)? Irrelevant authority cites someone who might be an authority in topic A in the entirety different topic or context B, where he is not an authority. Ipse dixit is making a statement without authority. So, citing Stephen Hawking (an expert in science) to “debunk” religion is an appeal to irrelevant authority. Stephen Hawking making blanket statements dismissing religion are ipse dixit.

The person who says that “the Pope falsely teaches X” and expects everyone to accept it as true without question is making an ipse dixit statement. This is why (for example) I point to the Church teaching and actual statements by the magisterium when I say “we must do X.” This is also why I insist on accusations against the Pope be proven based on the proper interpretation of what he says/does vs. the proper interpretation of what past teaching is¥. Sure, one might object validly to my being imprecise on how many critics (I always mean “some critics”), but I always try to study how the Church interprets past teachings and cite where I draw my conclusions from. I certainly don’t expect anyone to accept something on my say-so alone.

The problem is: what passes for “proof” against the Pope these days have no basis in fact but only in bare assertions. Claiming that the Pope is a “heretical NWO€ socialist Peronist etc. etc. etc.” is an ipse dixit clam. The accuser simply lacks the authority to make such a declaration based on his reading of Church teaching.

Conclusion

These are neither the only fallacies nor the only attacks used against the Pope, but they are current ones used since the Amazon Synod. In pointing out that they are logical fallacies, I show that the reasoning used to accuse the Pope do not prove their point.

To be proven logically true, the premises must be true and the logical form must be valid. The arguments used against the Pope meet neither criteria and should not be accepted by the faithful.

_________________

(§) Keep in mind that many anti-Catholics come from this background. That doesn’t prove that this individual is one (that would be the fallacy of division), but personal biases do need to be considered before accepting non-Catholic claims against Catholics.

(@) Before anyone should accuse me of personal animosity against them, I always found Fr. Pacwa’s talks enlightening and personally favored Cardinal Burke to become the Pope in the 2013 conclave (I had never heard of Cardinal Bergoglio before he became Pope). My current concern with them comes from statements that they made which might be interpreted as being at odds with the respect and obedience always expected towards Pope Francis’ predecessors.

(#) I don’t believe they have any intention to claim magisterial authority against the Pope in their statements.

(*) I have been told, but cannot independently verify, that the use of italics (which the Pope’s statement used) in Italy serves the same purpose as scare quotes in the United States.

(¥) Other examples might be the “Spirit of Vatican II” Catholics who argue that a certain passage “allows” them to dissent from a Church teaching because the latter teaching “contradicts” Vatican II. They don’t have the authority to interpret Vatican II contra the Pope.

(€) I suspect many of the people who cry “socialist” based on the Pope’s denunciation of abuses in capitalism have never read Pius XI in his denunciations of the abuses in capitalism.

No comments:

Post a Comment