The Catholic Church was established by Jesus Christ and given the authority and mission to bring His salvation to the entire world, “

teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you” (Matthew 28:20). When the Church teaches, it is with His authority (Matthew 16:19, 18:18) and rejecting the teaching of the Church is rejecting Him (Matthew 18:17, Luke 10:16). Indeed, He warns that “

Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only the one who does the will of my Father in heaven” (Matthew 7:21).

This obedience is not simply limited to the

ex cathedra teachings. We are also obligated to give religious submission of intellect and will to the ordinary teaching authority of the Pope and bishops teaching in communion with him (cf.

Canons 751-753,

Lumen Gentium 25,

Humani Generis 20 among others). If we knowingly do not accept this, we are heretics and schismatics.

The political field exists as a manner of agreeing how best to govern. In many circumstances, the government does enforce the common good through authority given it by God. As St. Paul (Romans 13:1-7) points out:

Let every person be subordinate to the higher authorities, for there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been established by God. Therefore, whoever resists authority opposes what God has appointed, and those who oppose it will bring judgment upon themselves. For rulers are not a cause of fear to good conduct, but to evil. Do you wish to have no fear of authority? Then do what is good and you will receive approval from it, for it is a servant of God for your good. But if you do evil, be afraid, for it does not bear the sword without purpose; it is the servant of God to inflict wrath on the evildoer. Therefore, it is necessary to be subject not only because of the wrath but also because of conscience. This is why you also pay taxes, for the authorities are ministers of God, devoting themselves to this very thing. Pay to all their dues, taxes to whom taxes are due, toll to whom toll is due, respect to whom respect is due, honor to whom honor is due.

The exception, however, is when the government tries to carry out what the Church which teaches with God’s authority. As Peter told the Sanhedrin, “We must obey God rather than men” (Acts 5:29). When the Church teaches that X is required or Y is forbidden, the state that refuses to do X or demands we do Y is demanding that we render what is God’s to Caesar (see Matthew 22:21). Nor can we be silent over what does not directly impact us but the Church condemns (See Matthew 25:41-46). As St. Caesarius of Arles points out (Sermon 157), if it’s wrong to do ignore the suffering, what will become of us if we participate in the evil:

Vatican II (Apostolicam Actuositatem #5) tells us:

Christ’s redemptive work, while essentially concerned with the salvation of men, includes also the renewal of the whole temporal order. Hence the mission of the Church is not only to bring the message and grace of Christ to men but also to penetrate and perfect the temporal order with the spirit of the Gospel. In fulfilling this mission of the Church, the Christian laity exercise their apostolate both in the Church and in the world, in both the spiritual and the temporal orders. These orders, although distinct, are so connected in the singular plan of God that He Himself intends to raise up the whole world again in Christ and to make it a new creation, initially on earth and completely on the last day. In both orders the layman, being simultaneously a believer and a citizen, should be continuously led by the same Christian conscience.

Because of this, we must listen to the Church when she teaches and “penetrate and perfect” the temporal order. But a dangerous attitude is arising among Catholics who used to pride themselves as faithful Catholics. That danger is treating the

teaching of the Church as a “prudential judgment” (in a

complete abuse of the term) or “interfering in politics” as if the bishops were corruptly abusing their authority to demand that we vote for a specific political party.

But that is not what they are doing. They are saying it is evil to support or be indifferent to abortion, same sex “marriage,” or the inhumane treatment of immigrants regardless of legal status. As Gaudium et Spes #27 puts it:

Furthermore, whatever is opposed to life itself, such as any type of murder, genocide, abortion, euthanasia or wilful self-destruction, whatever violates the integrity of the human person, such as mutilation, torments inflicted on body or mind, attempts to coerce the will itself; whatever insults human dignity, such as subhuman living conditions, arbitrary imprisonment, deportation, slavery, prostitution, the selling of women and children; as well as disgraceful working conditions, where men are treated as mere tools for profit, rather than as free and responsible persons; all these things and others of their like are infamies indeed. They poison human society, but they do more harm to those who practice them than those who suffer from the injury. Moreover, they are supreme dishonor to the Creator.

If the political party we favor supports one or more of these evils, we must oppose the evil, not point to the evil of the “other party” as worse and, therefore, justify the evil of our own party as unimportant in comparison. We cannot (if we are Democrats) downplay the evil of our party supporting abortion because our opposing the moral evil of the immigration policy. Nor can we, if we are Republicans, downplay the evil of our party’s role in the immigration policies because we oppose the evil of abortion [§].

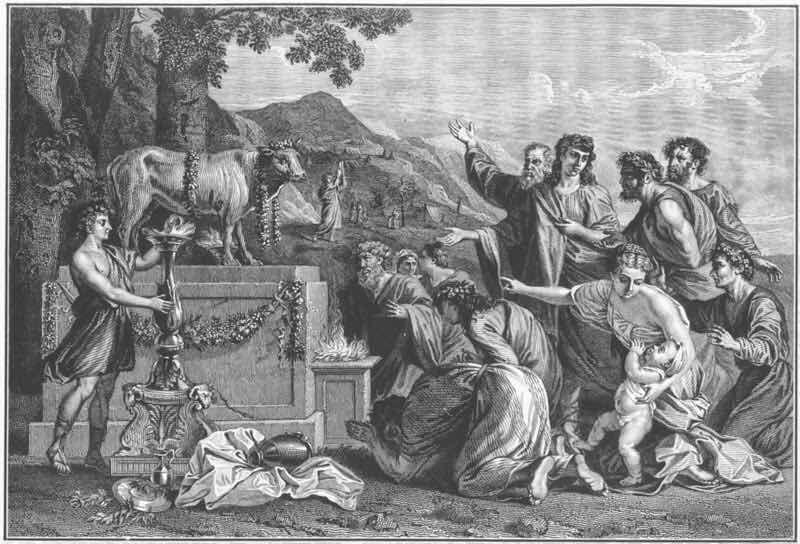

The problem is, when the Pope or the bishops of this country [#] condemn an evil act or intent that is a political plank in a party platform, we automatically assume they are “getting involved with politics” instead of acting as the successors of the Apostles. By refusing to consider that the party or the candidate we favor as being evil in the eyes of God, we risk turning the party or candidate we favor into an idol, acting with a dual allegiance forbidden to us.

When our political party embraces something that the Pope and bishops condemn as evil, we have a choice: to fight to overturn the evil in our party, or to leave the party. In the first option, Archbishop Chaput wrote about abortion, in 2004, something that applies to every grave evil:

My friends often ask me if Catholics in genuinely good conscience can vote for “pro-choice” candidates. The answer is: I couldn’t. Supporting a “right” to choose abortion simply masks and evades what abortion really is: the deliberate killing of innocent life. I know of nothing that can morally offset that kind of evil.

But I do know sincere Catholics who reason differently, who are deeply troubled by war and other serious injustices in our country, and they act in good conscience. I respect them. I don’t agree with their calculus. What distinguishes such voters, though, is that they put real effort into struggling with the abortion issue. They don’t reflexively vote for the candidate of “their” party. They don’t accept abortion as a closed matter. They refuse to stop pushing to change the direction of their party on the abortion issue. They don’t reflexively vote for the candidate of “their” party. They don’t accept abortion as a closed matter. They refuse to stop pushing to change the direction of their party on the abortion issue. They won’t be quiet. They keep fighting for a more humane party platform—one that would vow to protect the unborn child. Their decision to vote for a “pro-choice” candidate is genuinely painful and never easy for them.

(Render Unto Caesar)

If we look at his words as “Democrats bad, Republicans good” (or look at the denouncing of our immigration policy as “Democrats good, Republicans bad”), we’ve missed the point. What it means is when our party chooses evil, we must fight to change our party if we choose to remain in it—NOT to condemn our Church for pointing out that evil. Not saying “the other party is worse.”

God desires the salvation of all. That includes Trump and Ocasio-Cortez. It includes McConnell and Pelosi. We have to convert all the world to Him, not convert all the people to our preferred political party, and especially not demand the Church embrace our party.

If we will not obey the Church, we will reject from Him who sent His Church. Then He will say about us, “Bind his hands and feet, and cast him into the darkness outside, where there will be wailing and grinding of teeth.” (Matthew 22:13). And when He does so, there will be no excuses to justify us at the final judgment.

________________

[§] To avoid the accusation of bias (Succeed or fail, I try to keep my blog non-partisan) I put the party names in alphabetical order and used the first person plural with both to avoid giving the impression of siding with one over the other.

[#] Being an American myself, I write about what I know politically. I would hope that the general ideas work anywhere, but I don’t pretend to know the nuances of the politics in another nation.